Dungeons and Dragons is a role-playing tabletop game with a core emphasis on the interpersonal interactions between players, and between a dungeon master and the players. The role of the Dungeon master is essential to every gaming session of Dungeons and dragons, as you are responsible for setting up the stage on which the players express themselves.

You are the world, your player’s senses, and the consequences of their actions. Also, you are representing the world’s inhabitants, be it friendly bartenders, indifferent bystanders, or menacing monsters. You are all this, and more, when the situation demands it. Considering this, you will often find yourself carrying the weight of the table, for the untold truth is that your skill as a dungeon master is integral to a good session, but it doesn’t insure one. With all this said, no doubt, leading a game may seem daunting, and it is, but I assure you, it is incredibly rewarding, as is the undertaking of becoming a good DM. However, before we become good, let’s delve deeper into the hidden intricacies of the Dungeon master role.

First steps.

There are two key ingredients to being a Dungeon master; people willing to play, and time. I don’t want to understate the challenge of connecting these two, but imply the low introduction cost of this particular hobby.

My very first experience with DnD was in the role of the Dungeon master.

It started with two of my dearest friends, lying in our apartment bored out of our minds. I recalled watching a DnD game online and we happened to have a dice set on us, so I suggested we try. They were quick to accept, and it turned into a forty-hour-long marathon. All I had planned was a training session with Master Roshi. They ended up conquering half of the Azerothian Empire. They were hooked as I kept on improvising story beat after story beat. After thirty hours, they took a power nap and I scrapped up a bit of preparation. As soon as they woke up we burned through my prep in an hour, leaving me stranded with nothing but improvisation at my disposal, again. We were fueled by passion and energy drinks. They loved it. I loved it. We stank, it was great.

It was also an introduction to the game I wouldn’t recommend you try, but it was our start. Now we are older, somewhat smarter, and the passion we had long since dimmed down. We limit our sessions to under a day.

Marathon, not a sprint

What I want to impart to you is its accessibility. All we had was a single dice set, and even that is optional with mobile applications that all but play the game for you. There are a thousand tips and just as many tippers out there, poised to make you into the best Dungeon master the world has ever seen, and it is all just so overwhelming. Being a good DM is nothing short of turning water into wine, but I advise you to acknowledge the time investment and experience it requires. Start small. Soon you’ll be surprised at how far you’ve come since your first session. Advanced tips will help you only after you create yourself a solid foundation to build upon.

Prepare, but also prepare to be surprised…

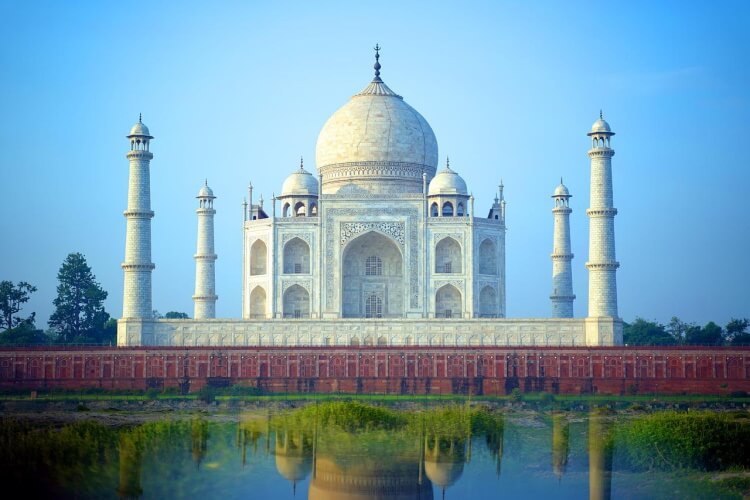

Before your players start adventuring, you’ll have to frame them into a scene. Your opening statement will always be a description. Introduction into the setting, the world, the antagonist, or this particular session, almost always follows the same line of questions. What would the player’s senses tell them? It’s the setup before you ask the age-old question; what do you do? Help them share your image of that marble-white palace, the smell of the spice market, or the sting of frigid winter wind on their skin. What you give the players here is what most of their actions will be based upon.

This is where preparation comes in. Your written descriptions will always sound and feel far more vibrant than whatever you can muster on the fly. If you feel you don’t have the literary spirit on your side, practice the ancient art of mimicry. So long as you don’t intend to monetize your game, I would urge all Dungeon masters to borrow and steal to their heart’s content. It will make your first steps easier.

You will need all the inspiration you can get. Write down descriptions of majestic mountain ranges, gloomy forest thickets, and shabby run-down drawbridges. Picture of a bald pirate with an eye patch swinging a scimitar. Mine. A port tavern with anchors used as table legs. Mine. Monks trading punches in the center of a flowering meadow. Mine. Mine. Mine. Build a library of sorts, a mind palace. A fountain of ideas to pull those pesky descriptions from when all else runs dry. It will help build confidence for when you stand before the table pretending you know all the answers. The trick is not letting them know that in the end, you are only pretending to know.

Fairness brings all the boys to the yard.

Fairness is a difficult topic to breach. It’s also paramount we do. As we mentioned before, your responsibility is of creating a stage for the players. You are the world, and you have the power to bring down terrible misfortune on your players. Nay, you must bring, in order to create dramatic tension. It’s a thin line to balance.

For instance, say we have a gaping chasm to jump over. Should an unfortunate roll of the dice result in character deaths? Should a casual evening stroll on the parapet lead to an encounter with an Ancient dragon?

Reality is yours to command, this everybody knows, which is why it’s important to develop a solid relationship with the players. You will have to warm them to your cause, and show them they can trust you. The world, therefore, must respond to the players with consistency, precisely so they can learn what to expect, and inspire them to participate and explore their options without the fear of unforeseen repercussions.

Don’t tell a story, ignite one.

You may have heard of the term, inciting incident. It’s often used in other storytelling media as a plot-advancing device, a call to adventure. However, in DnD, the story is not yours to tell, but a product of cooperation between you and the players. I cannot stress this enough. It’s what turns your role from an uphill battle into a casual stroll. Story elements should be sprinkled like sparkles to be manipulated later, once the party is hooked. I can’t deny the need for an overarching theme for your campaign, but ask that you allow for detours from the narrative railroad.

Adapt, improve, overcome.

All things considered, being a Dungeon master is an experience to be had. Expect to walk out from some sessions with a newly grown sympathy towards kindergarten teachers, as well as walking out with a feeling of accomplishment that will swell into the next day, throughout the week. One way or another, it’s not for the faint of heart.

The important thing is to start simple and to simply start.

You can lead a game for a single friend, perhaps he’ll ask for more. Know that improvisation is required, but avoidable to a degree. It’s not something to fret about, just don’t embrace it too much.

There is no one size fits all approach, and for the best. Whatever keeps your players excited for the next session is proof of a job well done. Sometimes it might mean taking a backseat or missing out on the spotlight, but it comes with the craft. A craft that has a skill ceiling, it just hasn’t been reached, or perhaps, never will be. Come and find out.

This guide is the first part of a three-part series in which we will explore what else you can hide behind the Dungeon Master screen.